Handling Multi-Part Maps in Azure Durable Functions

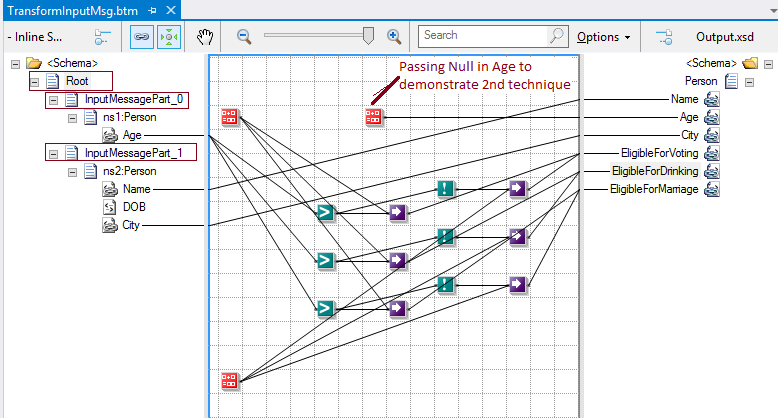

BizTalk Multi-Part Maps

I have been working with BizTalk Server since the 2010 version and have recently started to migrate orchestrations from BizTalk Server 2016 to Azure iPaaS using Azure Durable Functions. A common pattern found in BizTalk orchestrations is the content enrichment pattern which takes a payload and enriches it by looking up additional referential data in external data sources to provide the target system with all the required data.

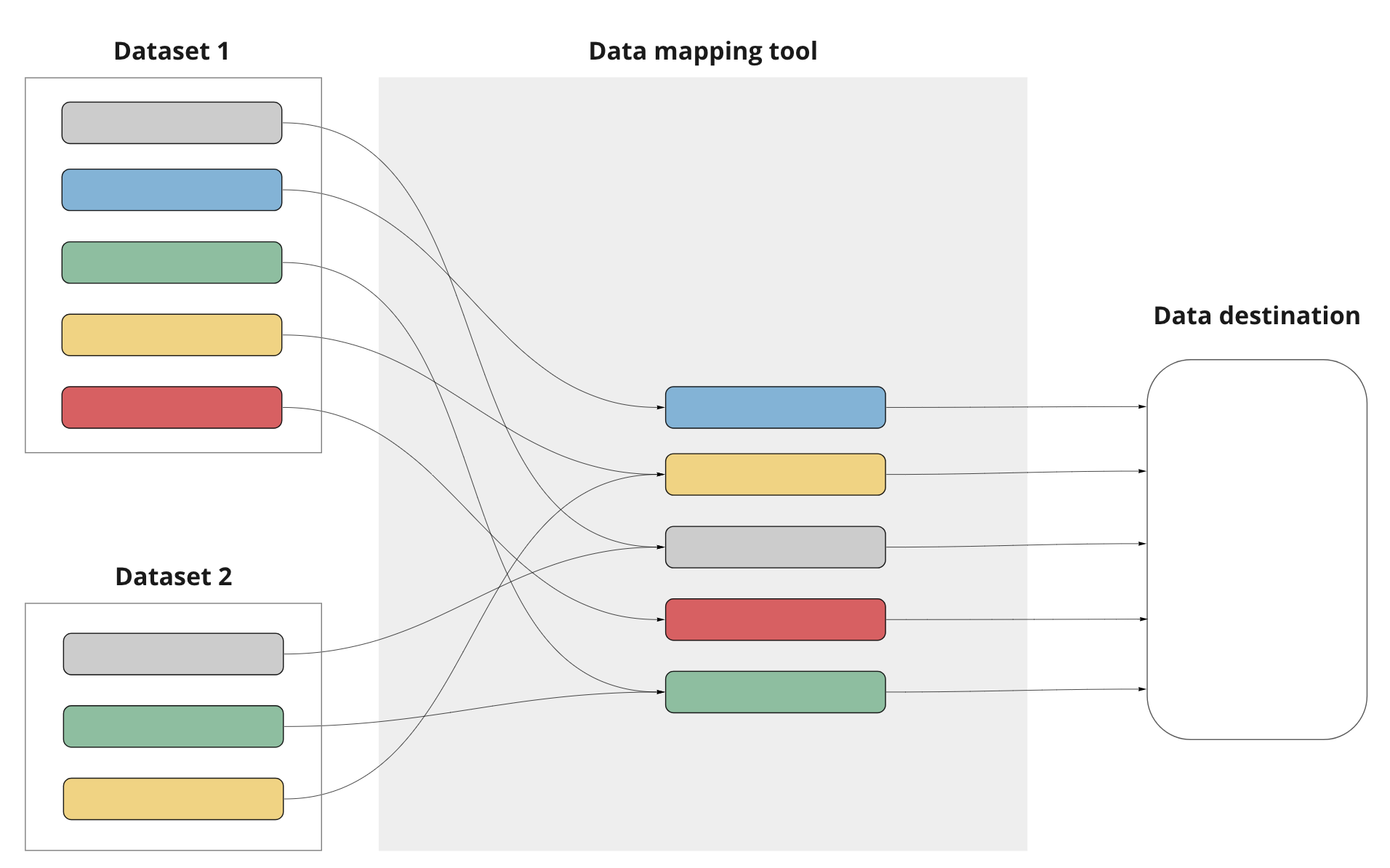

In BizTalk, one way this is achieved is by using multi-part maps to combine multiple messages into a single message to be then passed onto the target system containing all the required data.

In this post I’ll demonstrate the approach I took in recreating multi-part maps using Azure Durable Functions and AutoMapper.

The Tools

What are Durable Functions?

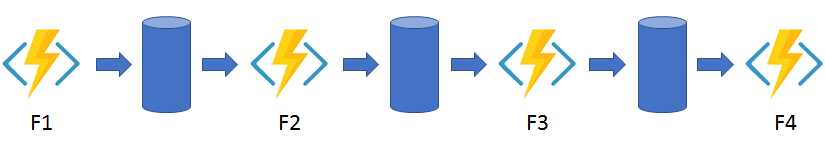

Durable Functions are an extension of Microsoft’s existing serverless technology, Azure Functions. Microsoft has a great overview article on Durable Functions. By way of a summary, Durable Functions manage a stateful workflow of activities to break orchestration logic into smaller steps and easily manage and monitor the state of those steps.

This is another really useful article which goes into a bit more detail than Microsoft’s overview about what’s under the hood of Durable Functions.

What is AutoMapper?

AutoMapper is an open-source, object-oriented mapper service with an emphasis on convention to minimise explicit mapping configuration. The developer, Jimmy Bogard, provides thorough documentation on how to set up AutoMapper for both simple and complex scenarios. I’ve used AutoMapper in many projects over the years as it also allows for the mapping configuration to be separated in your code into profiles for better organisation as well as reuse. Jimmy Bogard also has a blog with a post on AutoMapper usage guidelines.

Durable Function Sample

The rest of the post will be going through the sample GitHub repo I’ve prepared. The sample has a HTTP Trigger which takes a payload which, after retrieving additional data, maps the various objects into a single object which is returned to the user. For clarification, in a real-world scenario, the HTTP trigger would typically not return the result of the orchestration as a synchronous operation.

Models

The sample contains 4 models:

- Pupil - This is the model of the HTTP post body

- YearGroup - Represents 1 source of external related data

- School - Represents a second source of external related data

- PupilExport - This is the model of the output which comprises of the previous 3 models

The orchestration

The first step is receiving the payload from the HTTPTrigger. This done using the out-of-the-box binding attributes with Pupil being deserialized from the HTTPRequest and passed to StartNewAsync.

[FunctionName("DurableFunction")]

[OpenApiOperation(operationId: "Post", tags: new[] { "DurableFunction" })]

[OpenApiRequestBody(MediaTypeNames.Application.Json, typeof(Pupil))]

[OpenApiResponseWithBody(HttpStatusCode.OK, MediaTypeNames.Application.Json, typeof(PupilExport))]

public async Task<PupilExport> HttpStart(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, "post")] Pupil pupil,

[DurableClient] IDurableOrchestrationClient starter)

{

// Function input comes from the request content.

string instanceId = await starter.StartNewAsync(nameof(DurableFunctionOrchestrator), pupil);

...

}

In the previous code block, notice await starter.StartNewAsync(nameof(DurableFunctionOrchestrator), pupil). The orchestration function is started by specifying the FunctionName. To avoid magic strings, I’ve used nameof to highlight naming issues at build time. In the orchestration function, we first retrieve the Pupil input.

[FunctionName(nameof(DurableFunctionOrchestrator))]

public async Task<PupilExport> DurableFunctionOrchestrator(

[OrchestrationTrigger] IDurableOrchestrationContext context)

{

var pupil = context.GetInput<Pupil>();

var yearGroup = await context.CallActivityAsync<YearGroup>(nameof(DurableFunctionGetYearGroup), null);

var school = await context.CallActivityAsync<School>(nameof(DurableFunctionGetSchool), null);

var pupilExport = await context.CallActivityAsync<PupilExport>(nameof(DurableFunctionBuildPupilExport), (pupil, yearGroup, school));

return pupilExport;

}

In a real-world scenario, the pupil variable could be provided as a parameter to an activity like below to use any data in the object to retrieve the additional data.

[FunctionName(nameof(DurableFunctionGetYearGroup))]

public YearGroup DurableFunctionGetYearGroup([ActivityTrigger] Pupil pupil)

{

...

}

The DurableFunctionGetYearGroup and DurableFunctionGetSchool functions simulate returning additional data to the orchestration. The 3 variables are then passed as a tuple to the final activity DurableFunctionBuildPupilExport. This activity then uses IMapper which has been injected into the class to map the multiple parts into a single object.

[FunctionName(nameof(DurableFunctionBuildPupilExport))]

public PupilExport DurableFunctionBuildPupilExport([ActivityTrigger] Tuple<Pupil, YearGroup, School> tuple)

{

_logger.LogInformation($"Mapping tuple sources to {nameof(PupilExport)}");

var pupilExport = _mapper.Map<PupilExport>(tuple);

return pupilExport;

}

Mapping profiles

There are 4 MapperProfiles to demonstrate how large multi-part maps could be broken down into smaller chunks to be more readable as well as developing smaller unit tests, however, this can also be achieved in a single profile. The below profiles map each part to the destination. These use the typical ForMember(d => d.Member, o => o.MapFrom(s => s.Member)) notation:

- PupilProfile

- SchoolProfile

- YearGroupProfile

The PupilExportProfile then chains the maps in the previous 3 profiles together to produce the final message. This is done using ConvertUsing((s, d, c) => {...} which creates an execution plan where the 3 parts of the tuple are mapped onto the destination object.

CreateMap<Tuple<Pupil, YearGroup, School>, PupilExport>()

.ConvertUsing((s, d, c) =>

{

d = c.Mapper.Map(s.Item1, d);

d = c.Mapper.Map(s.Item2, d);

d = c.Mapper.Map(s.Item3, d);

return d;

});

As mentioned, the profiles could be merged into a single profile where the source members are referenced from the tuple directly using s.Itemx.Member as shown below.

CreateMap<Tuple<Pupil, YearGroup, School>, PupilExport>()

.ForMember(d => d.PupilName,

o => o.MapFrom(s => $"{s.Item1.Forename} {s.Item1.Surname}".Trim()));

The resulting object is then returned as the response in the HTTPTrigger in the orchestration.

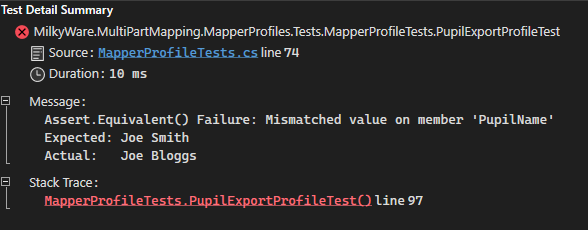

Unit testing

An xUnit project has also been added to demonstrate basic unit testing of the AutoMapper profiles making use of xUnits Asset.Equivalent() to compare the data within the expected and actual object, highlighting data differences. This is a new method as of xUnit 2.4.2.

An example of a basic xUnit test for AutoMapper is below:

[Fact()]

public void PupilProfileTest()

{

var input = new Pupil

{

Forename = "Joe",

Surname = "Bloggs",

DOB = new DateTime(2000, 1, 1)

};

var expected = new PupilExport

{

PupilName = "Joe Bloggs",

DOB = new DateTime(2000, 1, 1)

};

var actual = _mapper.Map<PupilExport>(input);

Assert.Equivalent(expected, actual);

}

Summary

In summary, we’ve introduced Azure Durable Functions and AutoMapper as a solution for replacing the orchestration functionality of BizTalk as well as providing the capability to create simple maps and complex, multi-part maps. This sample has used the basic sequence pattern in Durable Functions, however, this is just one of several supported patterns. We’ve also briefly looked at how AutoMapper can be used with xUnit to provide the same functionality as Microsoft.BizTalk.TestTools for unit testing maps.

Please feel free to share your comments below and thank you for reading.

Comments